- Resource

- BR1DGE

- Early Detection

- Pathophysiology

- Staging

- Monitoring

- Article

BR1DGE Symposium at EASD 2024

At the BR1DGE symposium at EASD 2024, leading experts shared new insights on early-stage (Stage 1 and 2) autoimmune type 1 diabetes (T1D), emphasizing the importance of screening for islet antibodies (IAbs) together with monitoring and education. Early type 1 diabetes identification can help to prepare people for a life with T1D.

This article is intended to be a summary only. Additional topics were covered in the live symposium in line with the applicable regulations but are not included on the BR1DGE platform.

Meeting Objectives

-

Describe the autoimmune pathophysiology of T1D and how disease progression can be quantified

- Understand the advantages of early screening for IAbs to detect T1D before the onset of symptoms

- Explore the recommendations of an international consensus on how to monitor presymptomatic people with confirmed IAbs

Speakers

Setting the Stage: Autoimmune Pathophysiology of T1D

Colin Dayan

"Autoimmune disease starts early, very early, and islet autoantibodies are a most robust marker for the beginning of the autoimmune attack on beta cells… it’s a reliable detection of an inevitable process."

When IAbs are first detected, the clock to T1D has already started ticking.

In the opening presentation, Professor Dayan provided a detailed exploration of the etiology and pathophysiology of T1D and emphasized that disease onset often starts many years before clinical onset (Stage 3).

- The etiology of T1D involves a complex interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental triggers, with the pathophysiology primarily driven by autoreactive T-cell-mediated attack on pancreatic beta cells.2-7

- As beta-cell destruction progresses, individuals move through three stages of disease: Stage 1 (normoglycemia) and Stage 2 (dysglycemia) are presymptomatic; Stage 3 corresponds with the clinical onset of T1D.8

- The incidence of T1D peaks between the ages of 10 and 14 years; however, in total, more people are diagnosed in adulthood than in childhood. Indeed, in 2021, of all new diagnoses of T1D worldwide, approximately 62% occurred in people aged ≥20 years.9

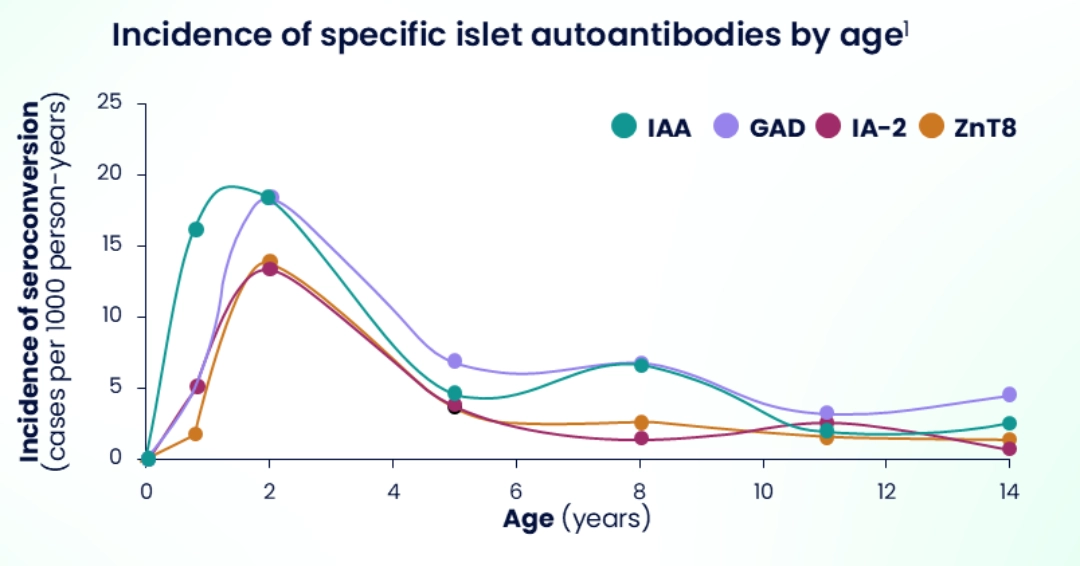

- However, T1D often begins far earlier in life. Seroconversion, peaking between 9 months and 2 years of age,1 is a clear marker of an autoimmune attack on insulin-producing beta cells.

- The presence of two or more IAbs is a reliable biomarker of the onset of T1D.2,4

- Detecting disease onset (autoimmunity) long before clinical onset provides a window of opportunity for those with presymptomatic T1D, potentially opening new opportunities for early monitoring and preparation.10,11

Shining a Spotlight on Screening: Clinical and Real-world Experience

Anette Ziegler

"Screening is feasible… as demonstrated by programs in many countries and can be integrated into regular care… we know that [T1D] can be detected early before the life-threatening conditions happen."

Early screening for IAbs is crucial to detect T1D before the onset of symptoms, enabling better glycemic control, reduced risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), and improved long-term outcomes.

Professor Ziegler delivered a clear and compelling message: early detection of presymptomatic T1D is a game-changer.

- Early detection of T1D provides advantages in terms of better glycemic control, reduced risk of complications (such as weight loss and DKA), and fewer days in hospital.1,2

- Early detection also enables families and caregivers to be prepared for what is to come, potentially alleviating the psychological stress associated with a diagnosis of T1D (Stage 3).3,4

- Several successful screening programs are already in place in many countries. Professor Ziegler shared that while initially targeting relatives of individuals with T1D is an option, the emphasis should shift to population-wide screening. Up to 90% of new cases of T1D arise without family history of T1D.5,6

Monitoring and Education for People with Early-stage Autoimmune T1D

Linda DiMeglio

"Regular monitoring for people with early-stage T1D needs to be personalized and performed according to the consensus monitoring guidance, and the psychological burden of early T1D should be assessed, and support offered to individuals and their caregivers."

Early-stage T1D requires personalized care in the form of regular monitoring, education, and psychosocial support to optimize outcomes.

In the final presentation, Professor DiMeglio explained how – in a significant development for early-stage T1D care – a newly released international consensus is reshaping how HCPs monitor people with confirmed IAbs.1

- A tailored approach to tracking disease progression is recommended, using tests such as glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), self-monitoring of blood glucose, and continuous glucose monitoring.1

- Regular monitoring should be conducted, ranging from every 3 months to every year, depending on the person's IAb status, metabolic status, and age.1

- The audience for the new guidance spans the entire care continuum. While PCPs may come to play a key role in initial autoantibody screening and monitoring, there always comes a stage at which referral to an endocrinologist or a diabetologist is essential. Clear handoffs between care teams are critical, supported by new International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes that capture the diagnosis of presymptomatic T1D to facilitate better monitoring, follow-up, and education.2-4

- But monitoring is not the whole picture; the consensus also emphasizes the human side of T1D care. Education and psychosocial support should be integrated into routine medical visits, ensuring individuals with presymptomatic T1D and their families are educated on symptoms such as DKA, and receive emotional support to cope with the psychosocial aspects.1

MAT-GLB-2405129-2.0 – 12/2024

Setting the Stage: Autoimmune Pathophysiology of T1D

- Ziegler AG, et al. Diabetologia. 2012;55(7):1937-43.

- Primavera M, et al. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:248.

- Verduci E, et al. Front Nutr. 2020;7:612377.

- American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl.1):S20-S42.

- Powers AC. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(8):e142242.

- Pugliese A. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016;17(Suppl 22):31-6.

- Clark M, et al. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1898.

- Insel RA, et al. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1964-74.

- Gregory GA, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(10):741-60.

- Besser REJ, et al. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2022;107:790-5.

- Hendriks AEJ, et al. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024;40(2):e3777.

Shining a Spotlight on Screening: Clinical and Real-world Experience

- Hummel S, et al. Diabetologia. 2023;66:1633-42.

- Bonifacio E, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12(6):376-8.

- Ziegler AG, et al. JAMA. 2020;323:339-51.

- Ziegler AG, et al. JAMA. 2020;323:339-51; supplementary appendix.

- Besser REJ, et al. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;1-13.

- Karges B, et al. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):1116-24.

Monitoring and Education for People with Early-stage Autoimmune T1D

- Phillip M, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(8):1276-98.

- University of Birmingham press release. Launch of new international medical code for presymptomatic type 1 diabetes. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/2024/launch-of-new-international-medical-code-for-presymptomatic-type-1-diabetes#:~:text=The%20new%20code%20presymptomatic%20type,in%20individuals'%20electronic%20health%20records. Accessed October 2024.

- PartBNews. April 22, 2024. Vol.38, Issue 17. https://www.thedoctors.com/siteassets/pdfs/pr-content/pbn042224.pdf. Accessed October 2024.

- JDRF Website article. 13.05.2024. https://www.breakthrought1d.org/news-and-updates/icd-10/. Accessed October 2024.