- Resource

- BR1DGE

- Early Detection

- Article

EASD 2025 Symposium Summary

During the BR1DGE Symposium at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2025 congress titled “A New Dawn in T1D: How Early Screening and Intervention Could Light the Way to Improved Clinical Outcomes”, experts discussed the importance of early detection in the management of autoimmune type 1 diabetes (T1D), risk factors for T1D, and different investigational therapeutic strategies in Stage 3 T1D.

This article is intended to be a summary only. Additional topics were covered in the live symposium in line with the applicable regulations but are not included on the BR1DGE platform.

Meeting Objectives

- Discuss the early detection of autoimmune T1D: significance in T1D management and collaborative actions for implementing screening programs.

- The importance of raising awareness about T1D to better understand misdiagnosis and minimize its occurrence.

- Explore the current investigational strategies aimed at preserving beta cell function.

Speakers

The Reality of Early Identification: The New Imperative in T1D Management

"We can reduce diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis significantly through early detection, and importantly, follow-up people once we detect the autoantobodies."

Dr. Anastasia Albanese-O'Neill discussed the benefits of early detection of T1D, challenges in diagnosis, and opportunities for sustainable advancements in early T1D detection.

- Individuals who have relatives with T1D have a 15-fold increased risk of developing T1D. Focusing on screening relatives alone misses nearly 90% of cases since most people with T1D have no family history.1

- General population-based screening programs may offer broader testing for presence of multiple autoantibodies (IAA, IA2A, GADA, and ZnT8A) and identify those at increased risk of T1D.1-3 Over 10 years’ follow-up, risk of Stage 3 T1D increased from 10–20% when a single autoantibody was detected to >70% when 2 or more autoantibodies were detected.4

- Early detection of T1D reduces risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at diagnosis and thus reduces the lifetime risk of severe micro/macrovascular complications. Early detection also gives individuals an opportunity to educate themselves and prepare for T1D management,1,5–9 facilitating reduced median HbA1c levels at Stage 3, decreased insulin requirements, decreased ketonuria, reduced psychosocial burdens and anxiety, and improved child QoL.10–13

- Previous studies reported significant reduction in DKA rates with early detection, from as high as 62% to below 5%.14

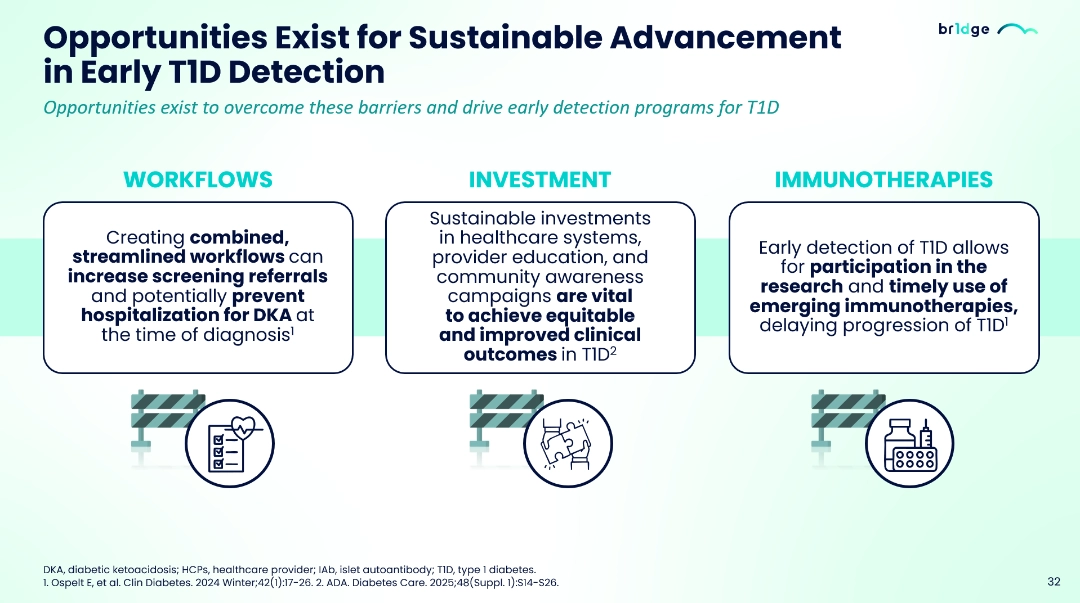

- Integrating T1D early detection programs into the healthcare system remains difficult due to limited healthcare coverage, inadequate workflow resources and infrastructure, higher screening costs and HCP uncertainty regarding the benefits of early detection.15–18

- Sustainable advancement in early T1D detection could be achieved with streamlined workflows, investment in healthcare systems, education and awareness and timely use of emerging immunotherapies.18,19

- Breakthrough T1D and INNODIA, BR1DGE platform and other platforms can help healthcare teams to adopt early identification programs, collaboration within multidisciplinary teams, educate clinicians on the benefits of early detection, and enable the implementation of national guidelines and practical early-detection strategies.2,17,20–23

Missed Signals – When T1D Goes Unrecognized

"Unfortunate reality is that no single clinical feature such as BMI or hyperglycaemia will allow us to confirm a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes"

- Prof Carmella Evans-Molina

Prof. Carmella Evans-Molina and Dr. Amir Tirosh discussed the misdiagnosis and importance of awareness in T1D and status of biomarkers for T1D.

- About 62% of new T1D cases were diagnosed in adults, about 40% of adults were misdiagnosed initially as T2D, and the risk of misdiagnosis appeared to increase with age.1–4

- Misdiagnosis or misclassification of T1D delays the start of appropriate therapies, which could lead to complications such as DKA. The risk of misdiagnosis increases up to 55% in adults who are aged ≥50 years.4

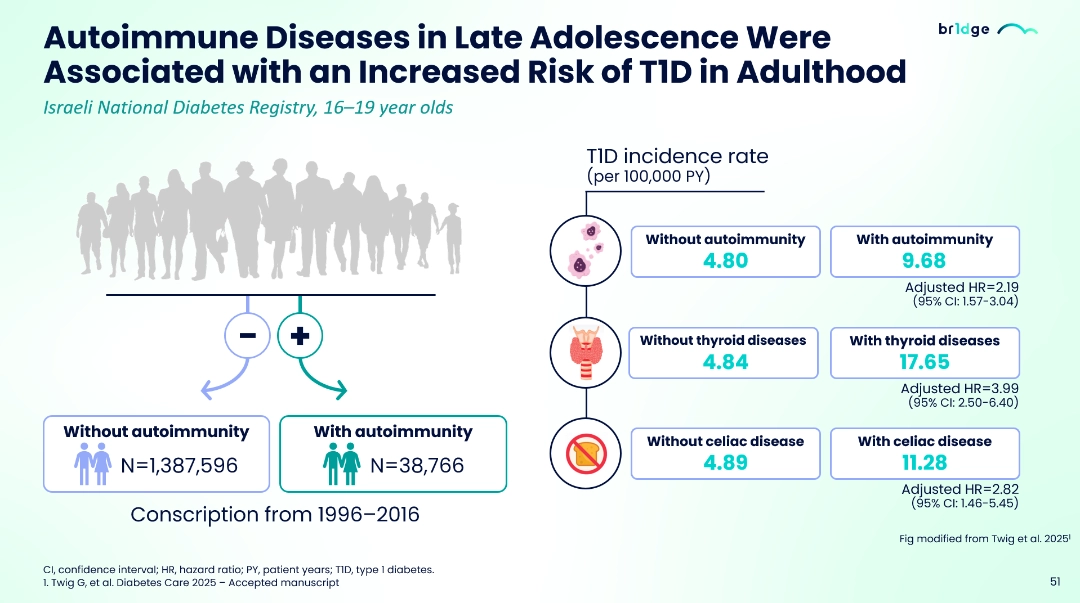

- About 30% of individuals with T1D have also reported one or more autoimmune diseases including autoimmune thyroid diseases and celiac disease; the risk of having T1D increases at least 2–4-fold in people who have a previous history of autoimmune condition.5-7

- No single clinical feature can definitively identify type 1 diabetes, emphasizing the need to consider multiple factors including personal or family history of autoimmunity, BMI (though not always reliable), elevated HbA1c levels, and response to typical type 2 diabetes treatments. 8 To distinguish between diabetes types, particularly in cases with ambiguous clinical presentation, clinicians can utilize C-peptide testing alongside autoantibody screening, and the AABBCC criteria.9,10

- Gestational diabetes in younger women can be a risk factor for T1D; approximately 12% of women with gestational diabetes have detectable autoantibodies, and over 75% of women with gestational diabetes who have more than 2 autoantibodies progress to Stage 3 T1D in < 5 years.11

- Clinical features of T1D and T2D overlap in adults and autoantibody testing is important when T1D is suspected. Increased awareness and improved diagnostic strategies that can reduce rates of misdiagnosis in T1D are needed.9

Beyond Diagnosis: Evolving Therapeutic Strategies in T1D

"The future of Type 1 diabetes looks to shift the focus to targeting the preservation of the beta cell function"

Prof. Colin Dayan presented the available clinical data of various immunotherapies candidates in different stages of T1D.

- While the glycemic monitoring tools for T1D management have improved individuals' quality of life, the burden of insulin management and adjustment and the fear of hypoglycemia still remain.1–4

- Benefits of preserving beta-cell in individuals with T1D, higher levels of remaining beta cell function were associated with longer time in range (TIR), reduced insulin requirements/doses, and reduced risk of complications such as retinopathy and nephropathy.5–8

- Different immunotherapeutic strategies are being investigated to preserve beta-cell function in Stage 2 and 3 T1D, which include targeting CD2, CD3, CD3/CD8, CD20, CD40L, IL12/23, TNF-α, or kinase proteins,9-15 and some of the recent Phase 2 and 3 trials reported delayed progression of beta-cell dysfunction in Stage 3 T1D.16

- Additionally, strategies such as islet transplantation, pancreas transplantation and transplantation of genetically modified allogenic donor islet cells into individuals with longstanding T1D (Stage 4) are being investigated, aiming to manage complications such as severe hypoglycemia and stabilize glucose levels.17

At the time of this presentation, Anastasia Albanese-O'Neill declared the following conflicts of interest: research funding - Breakthrough T1D receives unresctricted grant support from Sanofi, and speaker travel and honoraria donated to Breakthrough T1D.

At the time of this presentation, Carmella Evans-Molina declared the following conflicts of interest: received research funding in past from Lilly and Astellas Pharmaceuticals for investigator-initiated projects, speaker honoraria from Sanofi, PriMed, Diogenxy, Neurodon, Isla Pharmaceuticals .

At the time of this presentation, Amir Tirosh declared the following conflicts of interest: received research funding from Sanofi and Medtronic, received speaker honoraria from Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Dreamed Diabetes, Medtronic, and Radella Pharma; hold stocks in Radella Pharma, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

At the time of this presentation, Colin Dyan declared the following conflicts of interest: received research funding through charities and government/EU funding; Speaker/Consultant fees from Vielo Bio, Provention Bio, Sanofi, Amarna, SAB Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Shoreline Bio, Immunocore, Quell, and Vertex; and others from Vielo Bio, Provention Bio, Sanofi, Amarna, SAB Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Shoreline Bio, Immunocore, Quell, and Vertex.

MAT-GLB-2507088 - 1.0 - 12/2025

The Reality of Early Identification: The New Imperative in T1D Management

- Sims EK, et. al. Diabetes 2022;71:610-3.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Suppl 1):S27-49.

- Winter WE, et al. J Appl Lab Med. 2022;7:197–205.

- Ziegler AG, et al. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2473-9.

- Ziegler AG, et al. JAMA. 2020;323:339-51.

- Steck AK, et al. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(2):365–71.

- Cherubini V, et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:4197-202.

- Oron T, et al. Pediatric Diabetes. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/4238394. Accessed July 2025.

- Hoffmann L, et al. BMJ Open. 2025;15(1):e088522.

- Hummel S, et al. Diabetologia. 2023;66(9):1633-42.

- Bennet Johnson S, et al. Curr Diab Rep. 2011; 11:454-9.

- O’Donnell H. Stakeholder Engagement in Screening. Presented at: Childhood Diabetes Prevention Symposium; November 9–10, 2023; Aurora, CO, USA.

- Smith LB, et al. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(5):1025-33.

- Tribe. https://diatribe.org/early-diabetes-screening-kids-can-improve-quality-life. Accessed July 2024

- Pihoker C, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2312147.

- Pichardo-Lowden A, et al. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;25:448-55.

- Phillip M, et al. Diabetologia. 2024;67:1731-1759.

- Ospelt E, et al. Clin Diabetes. 2024 Winter;42(1):17-26.

- ADA. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Suppl. 1):S14-S26.

- BreakthroughT1D 2025 Available at: https://www.breakthrought1d.org/early-detection/#screening-options (Accessed July 2025).

- INNODIA Available at https://www.innodia.org/innodia-early-t1d-navigation-tool (Accessed July 2025)

- Haller MJ, et al. Horm Res Paediatr. 2024;97(6):529-45.

- Bell NR, et al. Can Fam Physician. 2017 Jul;63(7):521–4.

Missed Signals – When T1D Goes Unrecognized

- Gregory GA, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(10):741-60.

- ADA Diabetes Care 2025;48(Supplement_1):S27–S49.

- Holt RIG, et al. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2589-625.

- Munoz C, et al. Clin Diabetes. 2019;37(3):276-81.

- Mäkimattila S, et al. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1041-47.

- Frommer L, et al. World J Diabetes. 2020;11(11):527-39.

- Twig G, et al. Diabetes Care 2025 – Accepted manuscript.

- Diabetes Genes 2025 Available at: https://www.diabetesgenes.org/t1t2-classification/ (Accessed August 2025).

- Thomas N, et al. Diabetologia. 2023;66:2200-12.

- ADA Diabetes Care 2025;48(Supplement_1):S27–S49.

- Luiro K, et al. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023:14:1286375.

Beyond Diagnosis: Evolving Therapeutic Strategies in T1D

- Phillip M, et al. Diabetologia. 2024;67(9):1731-59 [simultaneously published in Diabetes Care. 2024;47(8):1276-98].

- ADA Professional Practice Committee. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Suppl. 1):S181-206.

- Singh A, et al. Eur J Cell Biol. 2023;102(2):151329.

- Hogrebe NJ, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(5):530-48.

- Fuhri Snethlage CM, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(7):1114–21.

- Latres E, et al. Diabetes. 2024 Jun 1;73(6):823-33.

- Taylor PN, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023 Dec;11(12):915-25.

- Harsunen M, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11(7):465-73.

- Jacobsen LM, et al. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(10):90.

- Ramos EL, et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(23):2151-61.

- Herold KC, et al. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;doi:10.1038/s41577-023-00985-4.

- Haller MJ, et al. Poster presented at the 50th ISPAD Annual Conference, 16-19 October 2024, Lisbon, Portugal. P-551.

- Tatovic D, et al. Nat Med. 2024;30(9):2657-66.

- Waibel M, et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2140-50.

- Gitelman SE, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(8):502-14.

- Herold KC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):603-13.

- Carlsson PO, et al. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(9):887-94.

.png/jcr:content/Slide%202%20(1).png)