- Resource

- BR1DGE

- Early Detection

- Article

BR1DGE Talks: Practical Insights into T1D Screening

During the BR1DGE Talks symposium at EASD 2025, experts discussed learnings from the implementation of population-level type 1 diabetes (T1D) screening programs.

This article is intended to be a summary only. Additional topics were covered in the live symposium in line with the applicable regulations but are not included on the BR1DGE platform.

Meeting Objectives

- Explore learnings from implementation of population-level T1D screening programs.

Speakers

Beyond a blueprint - Practical Insights into T1D Screening

In this panel Dr. Alice Cheng facilitated the discussion with Prof. Francesco Giorgino and Prof. Ezio Bonifacio focusing on population-level T1D screening programs, highlighting that over 50% of new T1D diagnoses occur in adults and 90% of people with T1D have no family history. She emphasized the importance of reconsidering pre-diabetes patients who might have stage 2 T1D rather than developing T2D.

- Screening programs in countries such as the UK, Italy, and Germany have shown success, especially in children and adolescents. Germany’s Fr1da study is cited as a successful model for population-wide screening.1 Infrastructure and stakeholder engagement—especially with pediatricians—are critical for success.

- Prof. Bonifacio stressed that relatives of people with T1D are at increased risk for T1D versus the general population2,3. He also discussed the importance of involving key stakeholders, particularly pediatricians, and demonstrating the clinical benefit beyond research purposes. Regarding adult screening, Prof. Bonifacio explained the challenges: fewer antibodies present in adults, longer disease progression periods, and the confounding presence of T2D.

- Prof. Bonifacio identified high-risk groups for screening, including relatives of T1D patients (10-15 fold higher risk) and those with other autoimmune diseases,4-12 while noting that 90% of T1D cases have no family history, Prof. Bonifacio recommended using multiple tests for confirmation and expressed interest in understanding what determines the varying progression rates to clinical diabetes.

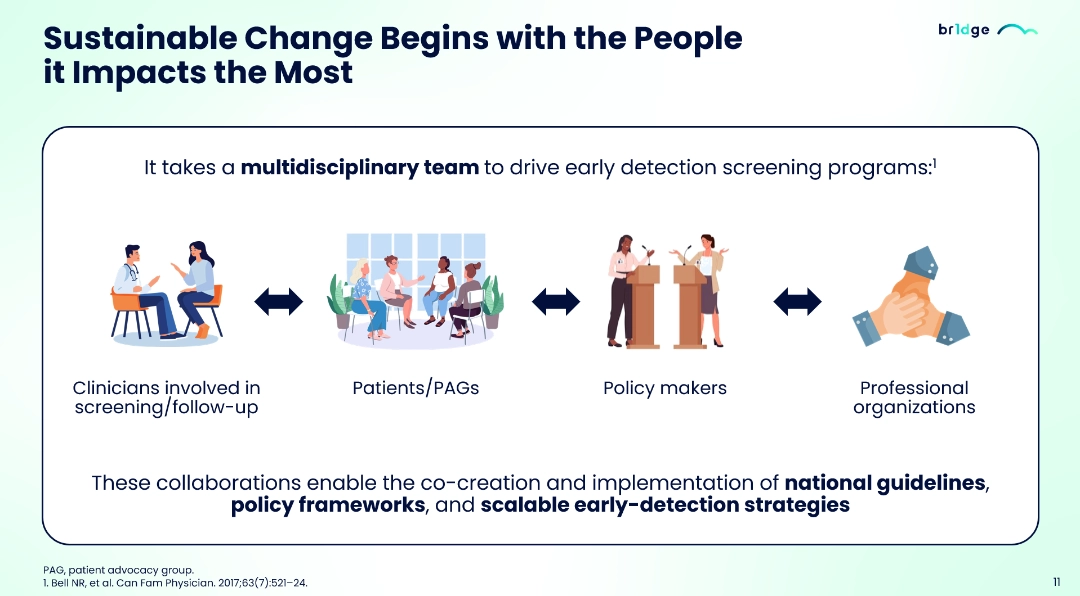

- Prof. Giorgino emphasized the importance of a multidisciplinary team to drive early detection screening programs. These collaborations enable the co-creation and implementation of national guidelines, policy frameworks, and scalable early-detection strategies.13

- Prof. Giorgino discussed the importance of alignment between pediatric and adult endocrinologists regarding scientific evidence and clinical protocols. He advocated for increased communication between learned societies and joint educational programs to build common knowledge about testing approaches and patient management.

- T1D is initially missed in up to 39% of individuals diagnosed and 77% of those are misdiagnosed with T2D. The panel discussed that screening should be considered for differential diagnosis in adults with abnormal glycemic status and risk factors for T1D.14-17

- Prof. Giorgino highlighted Italy's 2023 law establishing universal screening in the pediatric population across four regions, with plans to extend nationwide, primarily aimed at preventing DKA from undiagnosed diabetes.

- Prof. Giorgino referenced recent research showing that adults positive for just one antibody who develop dysglycemia progress to clinical diabetes at the same rate as antibody-positive children, emphasizing the importance of early detection across age groups.18

- The panel concluded that screening reduces the risk of severe complications such as DKA. Delayed screening, therefore, results in real and preventable harm to individuals at risk.19-21

Author Disclosure: the speakers are being compensated and/or receiving an honorarium from Sanofi in connection with this event.

MAT-GLB-2507087 - 1.0 - 12/2025

Beyond a blueprint - Practical Insights into T1D Screening

1. Leslie DR, et al. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2449-56.

2. Besser REJ, et al. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;23(8):1175-87.

3. Bonifacio E. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(6):989-96.

4. Anand V, et al. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(10):2269-76.

5. Insel RA, et al. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1964-74.

6. Phillip M, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(8):1276-98.

7. So M, et al. Endocr Rev. 2021;42(5):584-604.

8. Jacobsen LM, et al. Diabetologia. 2020;63(3):588-96.

9. Pöllänen PM, et al. Diabetologia. 2017;60(7):1284-93.

10. Suomi T, et al. EBioMedicine. 2023;92:104625.

11. Steck AK, et al. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):808-13.

12. Felton JL, et al. Commun Med (Lond). 2024;4(1):66.

13. Bell NR, et al. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(7):521–24.

14. Moore DJ, et al. Int J Gen Med. 2024:17:3003-14.

15. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S20-42.

16. Holt RIG, et al. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2589-625.

17. Munoz C, et al. Clin Diabetes. 2019;37(3):276-81.

18. Templeman El, et al. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(9):1–10.

19. Simmons K, EK Sims. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(12):3067–79.

20. Bell NR, et al. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(7):521–24.

21. Phillip M, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(8):1276-98.